Over the last couple of weeks, I've detailed some of the core offensive plays featured in some form or fashion in every Ohio State offensive gameplan. While the power, power read, and quarterback counters all are productive, no play is more critical to the success of the Buckeye offense than the inside zone read. As Kyle Jones at Eleven Warriors wrote in July, "[The inside zone read] truly acts as the starting point for the entire Buckeye offense."

The inside zone read is a core offensive concept for a significant number of college programs, and as Joe highlighted the Hokies featured the inside zone via the combination of Joel Caleb and Brenden Motley often in the Spring Game. The play features a zone blocking concept up front that allows the running back the freedom to identify a seam and run to it just like an inside zone, but adds an option concept that forces the defense to account for the quarterback both to the outside and on the inside on a midline version. Ohio State excels at executing the inside zone read. It's their primary running play, ignites their screen game, and sucks up linebackers and safeties to get big targets like tight end Jeff Heuerman (almost 19 yards per catch!) open in their vertical play-action passing game.

The inside zone read essentially is a hybrid of two core plays, the read option and the inside zone play. The quarterback makes a read on an unblocked defender and decides to either keep the ball or give it to the running back. If the running back gets the ball, he identifies a gap point behind an uncovered offensive lineman, plants his foot, and cuts off the lineman's butt into the second level.

The interesting thing about the play is that the offense basically tells the defense when they are running inside zone (or a play-action variant) most of the time. On most inside zone read action, the tailback aligns to the right or the left of the quarterback, but deeper in the formation. If the tailback aligns to the right or left of the quarterback at the same depth, the play will be outside zone, a power read, or a pass. If that tailback is tight to the quarterback and slightly behind him, it will be an inside zone or play-action. On occasion, the Buckeyes will also run the inside zone from the pistol, but Miller is much less of an option threat from that formation as he doesn't have the same forward momentum and angles at the mesh point.

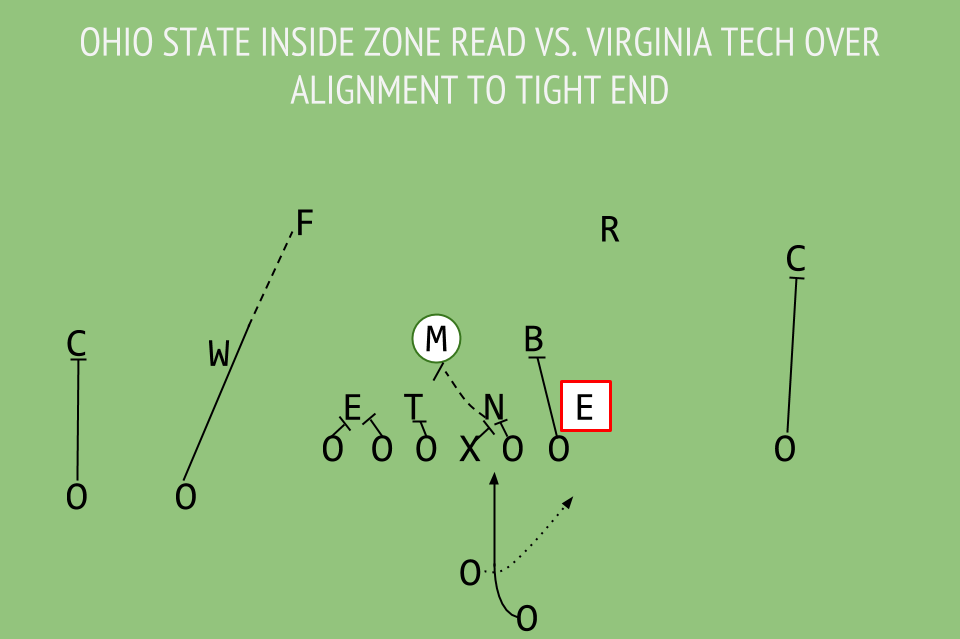

The Buckeyes can run the inside zone to the tight end or away from the tight end. The alignment of the tailback tells you where the running back will attack the line of scrimmage. If the running back aligns away from the tight end, he will aim for the inside leg of the center. If the running back aligns behind the tight end side (or there is no tight end) he aims for the opposite leg of the center, as the run to the strong side diagrammed below shows.

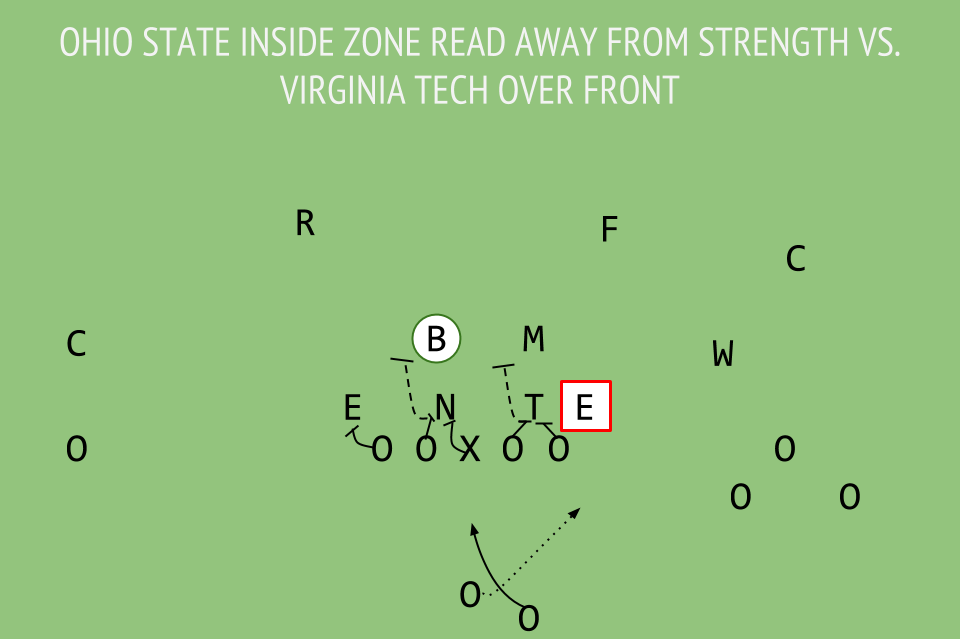

Here's an inside zone read run to the weakside.

Most defenses set the strength of the formation to the tight end side. The Hokies use an "over" front concept, meaning they shift their defensive line to the tight end. So, if the tight end aligns to the right, the Hokie three-technique defensive tackle will align on the outside eye of the right guard. The Buckeyes try to use formations and motion to let their back run at the three-technique defensive tackle and then cut into the bubble.

The blocking is simple for the offensive line. Everyone zone blocks to the three-technique side (away from the running back alignment.) Uncovered linemen are going to "zone block". That is help the nearest covered lineman (in the play side direction) drive their defender off the ball. Ideally, as the two offensive linemen hit the second level, one will come off the double-team to pick off a linebacker, or defensive back. The unblocked defensive end gets occupied by the quarterback's fake. If the defensive end crashes hard on the dive, the quarterback can pull the football and slip outside. If that end crashes too much (and Bud Foster has committed to stopping the dive and letting quarterbacks get their yardage), Braxton Miller can do serious damage on the end. Here, the Indiana end doesn't even crash too far inside, but Miller goes right around him.

The Spartan Adjustment

After two years of battling Urban Meyer's offense, many Big Ten opponents recognized that Ohio State prefers to run the inside zone read at the three-technique tackle. As an adjustment, many B1G defenses aligned their three-technique defensive tackle to the same side as the tailback, regardless of the formation strength. The tailback's most direct path takes him straight into the lap of the nose tackle. This also frees up the three-technique tackle to defeat a backside scoop of the offensive tackle, or force the offense to double team him. The double team leaves a linebacker unblocked.

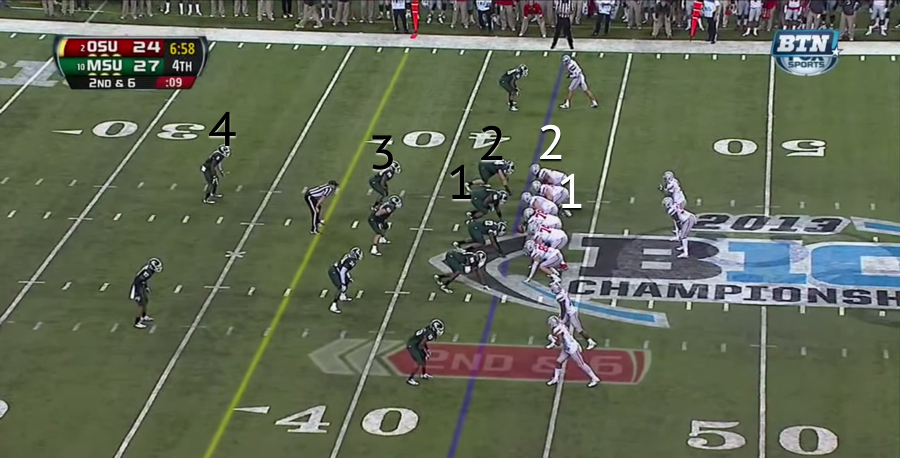

Let's examine how the Spartans adjustment jams up the hole.

Michigan State aligns the three-technique to the side of the tailback's alignment. The Spartans then use a gap-fit run blitz similar to the Hokies approach. The nose tackle stunts to his left into the guard-tackle gap, and the guard rides him outside. The three-technique stunts left across the face of the guard, forcing the center to block back and help him. Two blockers are now tied up with the three-technique. Both linebackers gap fit straight ahead, similar to how the Hokie linebackers fit on dive plays. Because the center is blocking back, and the right guard has ridden the nose outside, the left inside linebacker is unblocked and makes the tackle. The Spartans had varying degrees of success with this strategy, but they had enough that Urban Meyer ran the inside zone read less frequently than most of the games I have watched.

Meyer's Adjustment: Late Motion and the Hand-Clap Snap Count

To combat this adjustment by 4-3 over defenses, the Buckeyes will often line up in the Pistol formation with the back behind Miller. With the tailback a threat to run either strong or weak from the pistol alignment, the offense does not declaring one side or the other as the primary inside zone target. This prevents defenses from immediately aligning the three technique to the back. After starting his pre-snap signals, the quarterback motions the tailback to whichever side that the coaching staff feels presents the best opportunity for the play to be successful (most often away from the three technique.) On the signal, the back will motion to the quarterback's side, but OPPOSITE of the three-technique tackle. The defense either has to quickly motion to adjust (where, they can be caught out of position) or defend the play at a disadvantage.

The hand-clap signal is a really interesting tool. The quarterback can signal motion OR the snap either through a verbal command, a silent count, or a demonstrative hand clap. The clap is easy for the defense to see, and that is by design. The Buckeyes can start the play on the hand clap and can run the inside zone as a base play from the pistol (along with the power). So, if the defense uses the hand clap to time the snap, they could either be caught off-guard or jump offsides. Miller does an outstanding job mixing up those counts to keep the defense off balance. If they start to jump the snap on the hand clap, Miller can use it as a decoy and draw the Buckeyes offsides.

Here is an example. The Buckeyes start in the pistol, and the three-technique aligns to the called strength (our right.)

At the hand clap, the tailback shifts to (our left) the right side of the quarterback. In response, the Spartans shift over with the nose tackle sliding out to a three-technique, but Spartan linebacker (No. 28) doesn't slide to the appropriate one-technique alignment. When he reads inside zone read, he tries to fill down to the 1-gap, but the path he has to take gives the guard a better angle to seal him inside. The guard and tackle combine on a pancake block on the defensive tackle, the guard slides off to the linebacker, and the tailback slides right in the hole. The contain man has to take Miller on the option fake. The tailback slips untouched until the deep safety comes up in support. If the safety doesn't make the tackle, the tailback is off to the races.

While the Buckeyes made this adjustment often against the three-technique shift in the regular season, they seemed to run at the one-technique often against Michigan State, even when using the late tailback motion. I am not sure why. Either Miller did not read the front correctly and motioned the tailback to the wrong side, or Coach Meyer liked the matchup running at the one-techniques. It didn't make much sense to me. Let's take a look at the matchup.

As you can see, the Buckeyes try to execute the inside zone read with only two blockers to account for three defenders and a deep safety. The option fake doesn't account for one of the unblocked defenders as Miller is reading the end to the opposite side.

The Spartans outman the Buckeyes at the point of attack, and only Carlos Hyde's power and technique (getting downhill and pads forward as quickly as possible) make this play as short gain instead of a disastrous loss.

But, several times, the Buckeyes confused the Spartan front. Here again, the Buckeyes tailback motions from a slot position.

The Spartans adjust, but through miscommunication both defensive tackles align as a three-technique. At the snap, both linebackers blow through the 1-gaps trying to fill the space vacated by the defensive tackles. The left guard for Ohio State does a terrific job riding the Spartan linebacker (No. 40) inside, and Hyde makes a terrific cut. Given Foster's gap scheme and the way he teaches his mikes and backers to fit interior gaps, the inexperienced Hokie linebackers must take on blocks squarely and not be turned when the Buckeyes run the inside zone.

The Real Danger-play-action

The inside zone read isn't a sexy play. It is designed to be a steady ground gainer that can be run (and recognized defensively) from multiple sets. The excellence of the elite Ohio State athletes add big play explosiveness to the series.

But, the biggest threat from the inside zone read is play-action once the series is well established. The concept isn't far removed from Georgia Tech's spread option philosophy. Pound the defense again, again, and again. Make them familiar with a play. Then catch the linebackers and safeties cheating on a play and beat them with speed in space. The Buckeyes, however, have much more talent to bring to bear than Paul Johnson's Ramblin' Wreck.

The Buckeyes want to get their athletes in space, either by drawing the defense on the dive and then getting the ball out horizontally in the screen game, where their quick receiver/running back hybrids are matched up one on one with corners. One missed tackle and the Buckeye speed turns the boring wide receiver screen into a big play because the linebackers have to commit to stopping the inside zone read.

The other method of getting those talented receivers in space is through the vertical passing game. Most defenses are forced to commit at least six if not seven defenders to stopping the Buckeye running game. This leaves four defenders in the secondary (two of whom have alley run support if the front can't contain the inside zone). At the mesh point, both inside linebackers will commit to their gap fits at the line of scrimmage. In this situation, play-action with the four verticals concept can do major damage.

In the four verticals concept, the three receivers and tight end in the pattern all attack the cushion of their deep coverage. If the defender backpedals, the receiver can sit down in front of the defender because the linebackers have been sucked into the line of scrimmage. This puts tremendous strain on defensive backs, especially safeties in quarters coverage who are covering the receivers closest to the quarterbacks. If those safeties are playing inverted cover 2 (a Bud Foster favorite), they are coming forward at the snap to play short zones. Those slot receivers can then slip behind them, and your deep corners now have the responsibility of covering four receivers with only two players.

When Ohio State's inside zone read game is really working, they use the four verticals concept to deadly effect, especially with their big athletic tight end Jeff Heuerman. Heuerman averaged nearly 18 yards per catch last season, with many of those catches coming on vertical routes. Let's take a look.

Here, the Buckeyes fake the inside zone action against Purdue while running four vertical routes. Heuerman is aligned as a normal tight end.

Purdue's two inside linebackers commit on the dive. Both safeties support the deep threat to the outside, and Heuerman has a huge soft spot behind the linebackers right up the middle. This is a nice easy throw for Miller and a huge gain for the Buckeyes.

The inside zone read series and the play-action will determine how the Hokies fare in Columbus. The inside zone read puts tremendous pressure on inside linebackers, and the Hokies will be starting two inexperienced players at the position this season. While stunts and slants may confuse the equally inexperienced Buckeye offensive line, the Virginia Tech linebackers must not only take on blocks on the interior, shed those blocks, and make sure tackles against outstanding athletes, but they can't cheat and make themselves susceptible to play-action. And, even with all that pressure, there is Braxton Miller's ability to create big chunks of yardage on broken plays that strains the defense even further. For the Hokies to have success, the defensive line must take the dive away with their huge advantage at defensive tackle. The linebackers must be strong in their gap fits and tackling and force Miller to keep. The Hokies don't have the luxury of crashing defensive ends to help with the dive. If those ends crash, that frees up Miller to be one on one in the alley against the Hokie safeties. Jarrett and Bonner are good, experienced safeties, but they are already contending with the Buckeye deep threats up the seam, so their responses will be delayed. Also, as good as they are, Miller one on one against those safeties isn't a matchup that any defensive coordinator would be excited about. Miller is a special player. The option-nature of the play also means that it is incredibly difficult to use a spy except in obvious passing situations. It is too easy to either give the ball to the dive at the spy and run the spy out with the quarterback, or just use the quarterback counter to run away from him.

With almost no public access during fall camp, and very little blitzing in the spring game, it will be very interesting to see what kind of packages that Coach Foster develops for neutralizing the Buckeyes offense. However, the Hokie offense that we saw in the spring (inside zone with Joel Caleb, power with Marshawn Williams, and vertical concepts with Bucky Hodges) looked eerily similar to a simplified version of the Buckeye offense. After the offense had success in the next to last scrimmage before the spring game, Coach Foster adopted a hyper-aggressive approach that decimated the Hokie offense. In my next review of the series, I will examine how some Big Ten teams had success, and compare that to different possible approaches that Coach Foster could bring to the table against the favored Buckeyes.

Comments

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.

Please join The Key Players Club to read or post comments.